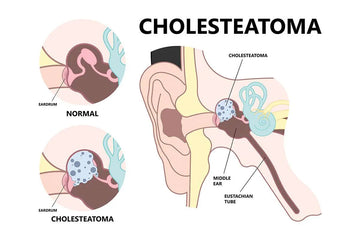

Cholesteatoma is a condition that affects the ear and can gradually lead to problems such as hearing difficulties and recurring infections if not managed. Although the name might sound like a type of tumor, it is not cancer. Instead, it is an abnormal growth of skin cells in the middle ear (the space behind the eardrum), which clumps together to form a lump or cyst that resembles a pearl. Over time, this growth can affect the delicate structures in the ear responsible for hearing and balance.

Understanding what a cholesteatoma is, how it develops, and the signs to watch for is helpful because early diagnosis and treatment can prevent future complications.

What is Cholesteatoma?

A cholesteatoma is an abnormal growth of skin cells that develops in the middle ear (the small air‑filled space behind the eardrum). Although it is sometimes described as a tumor, it is not cancer. Instead, it behaves like a cyst or sac that slowly builds up layers of skin cells and debris in a place they should not be. Over time, this growth can affect nearby structures and interfere with hearing and balance.

Types of Cholesteatoma

There are two main types, based on how and when they form:

• Congenital cholesteatoma

This type is present at birth. It occurs when skin cells become trapped behind the eardrum during early development. It may remain unnoticed for years, often discovered when a child begins to show hearing problems despite no history of repeated ear infections.

• Acquired cholesteatoma

This is the most common type and develops later in life. There are two main forms:

-

Primary Acquired

This develops when pressure inside the middle ear is not balanced properly, often due to Eustachian tube dysfunction (when the small tube connecting the middle ear to the back of the nose is not working well). Ongoing problems such as repeated ear infections (chronic otitis media) can cause parts of the eardrum to be slowly pulled inward, forming a small pocket (called a retraction pocket). Over time, this pocket collects skin cells and debris, creating a cholesteatoma.

As this growth enlarges, it can damage the tiny hearing bones (ossicles) and even erode nearby bone areas such as the tegmen mastoideum (a thin section of bone that separates the ear from the brain).

-

Secondary Acquired

This develops when there is a direct opening in the eardrum (an eardrum perforation). Through this opening, skin cells from the outer ear can enter the middle ear and begin to grow where they should not. Perforations may occur after repeated infections, injuries, blast trauma, or previous ear surgery.

Both primary and secondary acquired cholesteatomas can be challenging to treat because they have a limited blood supply, which makes them resistant to typical medical treatments such as antibiotics or steroid drops.

Characteristics and Symptoms of Cholesteatoma

A cholesteatoma often develops slowly, so symptoms may begin subtly and progress over time. Many people first notice minor ear problems that gradually become persistent. Recognizing these signs early can help prevent further damage.

Key Symptoms:

-

Progressive hearing loss

-

Hearing in the affected ear often worsens slowly as the growth damages the eardrum and the tiny bones (ossicles) that transmit sound

-

Persistent ear discharge (otorrhea)

-

Recurrent ear infections

-

Feeling of fullness or pressure in the ear

-

Occasional ear pain

-

Balance problems or dizziness

As the cholesteatoma enlarges, it can:

-

Damage the tympanic membrane (eardrum) and ossicles.

-

Disrupt the function of the Eustachian tube (the small tube that regulates air pressure in the ear).

-

In severe cases, it can erode the surrounding bone, such as the tegmen mastoideum (a very thin section of the temporal bone that forms the roof of the middle ear), or even expose the facial nerve or areas that help with balance.

Because the growth has a poor blood supply, treatments like antibiotics or steroid ear drops often provide only temporary relief.

Understanding the Audiogram

When we look at the hearing difficulties caused by a cholesteatoma, it’s helpful to examine an audiogram.

The audiogram above shows a moderate sensorineural hearing loss in the left ear and a moderate mixed hearing loss in the right ear:

Left ear (X marks):

Across most frequencies, the thresholds are around 35–55 dB, showing a consistent moderate hearing loss. Because this loss is sensorineural, it reflects changes in the inner ear or hearing nerve, which affect both volume and clarity.

Right ear (O marks):

Here we see a mixed hearing loss, a combination of conductive loss (issues in the middle ear, often due to the cholesteatoma’s damage to structures like the eardrum or ossicles) and sensorineural loss. The thresholds sit around 50–70 dB in some areas, meaning sounds must be much louder for the right ear to detect them.

The right ear shows damage in both the middle and inner ear, while the left ear shows inner‑ear damage only. Understanding this audiogram helps explain why someone might experience ongoing hearing difficulty, even when infections or discharge are treated, and it guides decisions on whether surgical intervention is needed to protect or improve hearing.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Doctors diagnose a cholesteatoma by taking a detailed medical history and performing a thorough ear examination.

Typical questions include:

-

How long have you had ear symptoms such as discharge, pressure, or hearing loss?

-

Whether you’ve had repeated ear infections, past ear surgery, or ear injuries.

Examination:

Using a special microscope (called an otomicroscope) or an otoscope, the doctor looks closely inside the ear. A cholesteatoma often appears as a white or yellow mass behind the eardrum, sometimes sitting in a pocket or behind a tear in the eardrum. If there is drainage, the doctor may gently clean it to get a better view. Facial movement and balance may also be checked, because a large growth can affect nearby nerves or balance organs.

Hearing tests:

An audiogram (a hearing test) is usually done to see how much hearing is being affected. Testing includes pure tone audiometry, speech testing and bone conduction audiometry.

Imaging:

Sometimes a CT scan (a detailed X‑ray of the ear bones) or MRI (a scan that shows soft tissues clearly) is ordered if the doctor needs to know how far the growth has spread or to check for complications.

Surgery is the main treatment.

Because a cholesteatoma keeps growing and can slowly damage important parts of the ear, it cannot be cured with medicine alone. Ear drops or antibiotics may help control infection temporarily, but they do not remove the growth.

The goal of surgery is to:

-

Remove the cholesteatoma completely to stop further damage.

-

Repair the eardrum and, if possible, restore hearing by repairing or replacing the tiny hearing bones.

-

Create a safe, dry ear that is easier to care for in the long term.

Types of surgery:

-

A common approach is called tympanomastoidectomy, which involves cleaning the disease from both the middle ear and mastoid (the honeycomb‑like bone behind the ear).

-

The surgeon may keep the ear canal structure in place (canal wall up) for a more natural look and better hearing potential, but sometimes, for more extensive disease, they remove part of that wall (canal wall down) to make sure no disease is left behind.

After surgery:

-

Some patients may need a second procedure or follow‑up MRI scans months later to make sure no small pieces of cholesteatoma were left behind, as these growths can recur.

-

Regular ear cleaning and follow‑up with the ear specialist are often needed.

Although a cholesteatoma is not cancer, it can damage nearby structures over time. If left untreated, it can lead to worsening hearing loss, ongoing infections, balance issues, and, in rare cases, more serious complications involving the nerves or areas near the brain. Fortunately, with proper diagnosis and surgical treatment, most people recover well and maintain stable ear health with regular follow‑up.

With timely care and regular follow‑up, most people recover well and enjoy better, safer ear health.